Introduction

The nature of beauty has been debated for centuries, with philosophers, artists, and scientists exploring whether beauty is a subjective experience shaped by individual perception or an objective quality inherent in the world.

The Case for Beauty as Subjective

Subjectivists argue that beauty exists in the eye of the beholder and is influenced by personal experiences, cultural backgrounds, and psychological factors. This perspective suggests that what one person finds beautiful may not be appealing to another.

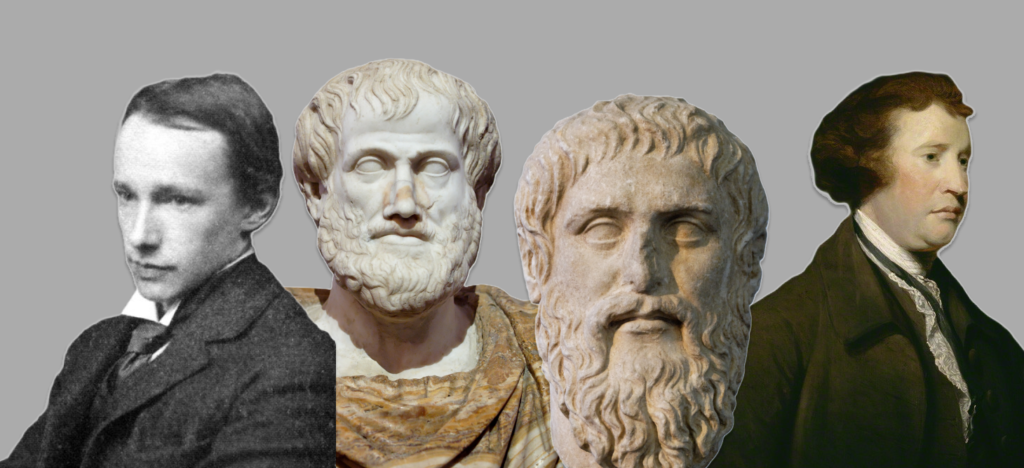

Key Philosophers Supporting Subjectivity:

- David Hume (1711–1776) –David Hume, in Of the Standard of Taste (1757), argues that beauty is not an inherent property of objects but exists in the mind of the observer. He maintains that aesthetic judgments are based on individual sentiment, making beauty largely subjective. However, Hume also acknowledges that not all opinions on beauty are equally valid, as this would lead to complete relativism. To address this, he proposes the idea of an “ideal critic”—a person with refined taste, extensive experience, and an impartial perspective—who helps establish aesthetic standards. These standards emerge from a historical consensus of admiration rather than from purely personal preference. Hume believes that good taste can be cultivated through exposure to great works and the development of critical faculties. While beauty remains a matter of perception, certain aesthetic qualities tend to be universally appreciated due to shared human responses. In this way, Hume strikes a balance between subjectivity and objectivity, arguing that while beauty depends on perception, refined judgment and cultural refinement can create a more structured appreciation of aesthetics.

- Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) –Immanuel Kant, in Critique of Judgment (1790), presents a nuanced view of beauty that blends subjectivity with a form of universality. He argues that beauty is not an objective property of objects but is instead rooted in the subjective experience of the observer. However, he differentiates aesthetic judgments from mere personal preferences by claiming that when we judge something as beautiful, we do so with the expectation that others should agree, even though beauty is based on feeling rather than logic or empirical knowledge. According to Kant, a true judgment of beauty is “disinterested,” meaning it is free from personal desires or practical considerations—it is appreciated for its own sake rather than for any function it serves. He also introduces the idea of “universal communicability,” suggesting that while beauty is subjective, it carries an implicit demand for universal agreement because it arises from common cognitive faculties shared by all humans. Unlike Hume, who emphasizes the role of experience and refined critics in shaping aesthetic standards, Kant insists that beauty is judged by an innate sense of harmony within the mind. In this way, Kant positions beauty as both subjective—since it arises from individual perception—and universally valid, as it is rooted in the shared faculties of human cognition.

- Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) – Jean-Paul Sartre, as an existentialist, takes a radically subjective stance on beauty, rejecting the idea that it has any inherent or objective qualities. In his broader philosophy, Sartre argues that meaning—including aesthetic value—is not found in the world but is instead created by individuals. Beauty, like all forms of value, exists only because human consciousness assigns it significance. This aligns with his concept of radical freedom, where individuals are free to define their own standards of beauty without relying on external authorities or universal principles. Sartre dismisses the notion of an ideal form of beauty, as found in Plato, or a shared cognitive structure for aesthetic judgment, as proposed by Kant. Instead, he sees beauty as a project of human subjectivity, shaped by personal experiences, emotions, and existential choices. This means that beauty is neither objective nor universally communicable—it is a purely individual phenomenon that varies from person to person. Sartre’s perspective implies that any attempt to establish a common standard of beauty is an act of bad faith, an inauthentic attempt to impose external meaning where none inherently exists. His existentialist approach ultimately reduces beauty to a matter of personal creation, where the observer is not just a passive recipient of aesthetic experience but an active participant in defining what beauty means.

Pros of Subjectivism:

- Acknowledges cultural and personal diversity in aesthetic preferences.

- Explains why beauty standards evolve over time.

- Accounts for emotional responses to art and nature.

Cons of Subjectivism:

- Leads to relativism, making it difficult to establish aesthetic criteria.

- Cannot fully explain why certain forms of beauty are widely recognized across cultures.

- Risks reducing beauty to mere personal preference without deeper significance.

The Case for Beauty as Objective

Objectivists argue that beauty exists independently of human perception and is determined by intrinsic qualities such as symmetry, harmony, and proportion. This view holds that some things are universally beautiful regardless of individual opinion.

Key Philosophers Supporting Objectivity:

- Plato (c. 427–347 BCE) – Plato takes an objective and metaphysical approach to beauty, arguing that it exists independently of human perception. In his theory of Forms, he posits that beauty is not merely a matter of opinion or sensory experience but an eternal, unchanging ideal that transcends the physical world. In Symposium, he describes a hierarchy of beauty, where individuals begin by appreciating physical beauty but, through intellectual and philosophical development, ascend toward the recognition of the Form of Beauty itself—a perfect, immutable concept that all beautiful things partake in. In Republic, Plato associates beauty with order, proportion, and harmony, reflecting his belief that true beauty is linked to the rational structure of the universe. Unlike Hume or Sartre, who see beauty as dependent on perception or personal creation, Plato maintains that beauty has an absolute existence, independent of individual experiences. However, he also warns that physical beauty can be deceptive, as it is only an imperfect reflection of the higher, eternal beauty of the Forms. This view makes Plato one of the strongest proponents of objective beauty, grounding it in a realm of perfect, unchangeable truths rather than subjective human experience.

- Aristotle (384–322 BCE) – Aristotle linked beauty to order, symmetry, and proportion, arguing that aesthetic pleasure arises from these objective qualities.Aristotle, in contrast to Plato, takes a more empirical and naturalistic approach to beauty, grounding it in the physical world rather than an abstract realm of Forms. In Poetics and Metaphysics, he argues that beauty is objective to some extent, as it is based on principles of order, proportion, and harmony—qualities that can be observed in nature and art. Unlike Plato, who sees beauty as an ideal separate from the material world, Aristotle believes that beauty exists within things themselves and can be studied through reason and experience. He emphasizes that beauty is not purely subjective but follows recognizable patterns, such as symmetry, balance, and clarity, which evoke pleasure in observers. However, he also acknowledges that perception plays a role, as different people may respond to beauty in varying ways. In Rhetoric, he notes that beauty is linked to function and purpose, meaning something is beautiful when it fulfills its intended role effectively. While Aristotle accepts that beauty has universal qualities, he does not argue for an absolute, metaphysical standard as Plato does. Instead, he sees beauty as a combination of objective structural qualities and subjective human experience, making his view a middle ground between strict objectivism and pure subjectivism.

- Edmund Burke (1729–1797) – Edmund Burke, in A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757), presents a psychological and emotional approach to beauty, distinguishing it from the sublime. Unlike philosophers who focus on beauty as a matter of proportion or form, Burke argues that beauty is primarily about the emotional response it evokes in the observer. He defines beauty as that which produces feelings of pleasure, love, and affection, often associated with qualities such as smoothness, delicacy, smallness, and gentle variation. In contrast, the sublime is linked to vastness, power, and even terror, inspiring awe rather than pleasure. Burke’s theory is largely subjective, as he sees beauty as dependent on human perception and psychological reactions rather than inherent properties of objects. However, he does recognize common patterns in what people find beautiful, suggesting that biological and cultural factors shape aesthetic responses. His emphasis on emotion and sensation rather than abstract principles marks a shift toward a more empirical and psychological understanding of beauty, influencing later aesthetic theories, including Romanticism.

- G.E. Moore (1873–1958) –G.E. Moore, in his work Principia Ethica (1903), approaches beauty from the perspective of ethical and philosophical realism, arguing that it is an intrinsic good that exists independently of human perception. Unlike Hume, who sees beauty as subjective, or Kant, who tries to balance subjectivity with universal judgment, Moore insists that beauty is an objective quality that contributes to human well-being in a way that can be known through intuitive knowledge. He applies his “naturalistic fallacy” argument, asserting that beauty cannot be reduced to natural properties like pleasure or proportion—it is a non-natural property that we recognize through direct experience. While beauty is related to aesthetic enjoyment, Moore holds that it has an independent value that makes the world better simply by existing. His approach aligns with ethical intuitionism, suggesting that beauty is a fundamental aspect of what is good and should be appreciated for its own sake. However, Moore does not provide a precise definition of beauty, instead emphasizing its role as an intrinsic good that is valuable regardless of personal preference or cultural influence.

Pros of Objectivism:

- Provides a stable foundation for aesthetic judgment.

- Explains why certain forms, patterns, and sounds are universally recognized as beautiful.

- Aligns with scientific studies on symmetry, proportion, and evolutionary preferences for beauty.

Cons of Objectivism:

- Struggles to account for cultural and historical variations in beauty standards.

- Can lead to aesthetic elitism, dismissing personal experiences and preferences.

- May overlook the emotional and psychological aspects of aesthetic appreciation.

The debate over whether beauty is subjective or objective remains unresolved, with compelling arguments on both sides. Subjectivists emphasize the personal and cultural factors that shape our perception of beauty, while objectivists argue that certain aesthetic qualities have universal appeal. In reality, beauty may be best understood as a combination of both perspectives—grounded in objective principles yet shaped by subjective interpretation. This dual approach allows for a richer understanding of aesthetic experience, embracing both universal structures and individual creativity.